Most of the time, people use the internet without ever thinking about how their devices actually “find” each other. Then something odd pops up—like a strange address in a log file or a number that looks almost right but somehow isn’t, such as 164.68111.161—and suddenly the behind-the-scenes stuff starts to feel a lot more important. If you’ve ever wondered how these addresses really work, this guide on the IPv4 address structure is for you.

In the main article about 164.68111.161, the focus is on a single invalid address and why it doesn’t follow the rules. Here, the goal is a bit broader: to walk through what a valid IPv4 address looks like, what each part means, and why a single out-of-range number can break everything. Along the way, this will connect with ideas from cybersecurity, testing, and even software versioning, so the bigger picture starts to make sense.

What Is an IPv4 Address, Really?

At its simplest, an IPv4 address is just a numerical label used to identify a device on a network. Every device that connects—laptops, phones, servers, routers—needs some kind of address so data knows where to go. In the IPv4 world, that address is written in a familiar dotted format like 192.168.1.10.

IPv4 has been around for decades and still carries a huge portion of the world’s internet traffic. Even though IPv6 is slowly taking over in some regions, IPv4 remains the “default mental model” for most admins, developers, and everyday users. That’s why, when something like 164.68111.161 shows up, it feels familiar but not quite right.

The Four-Octet Structure of IPv4

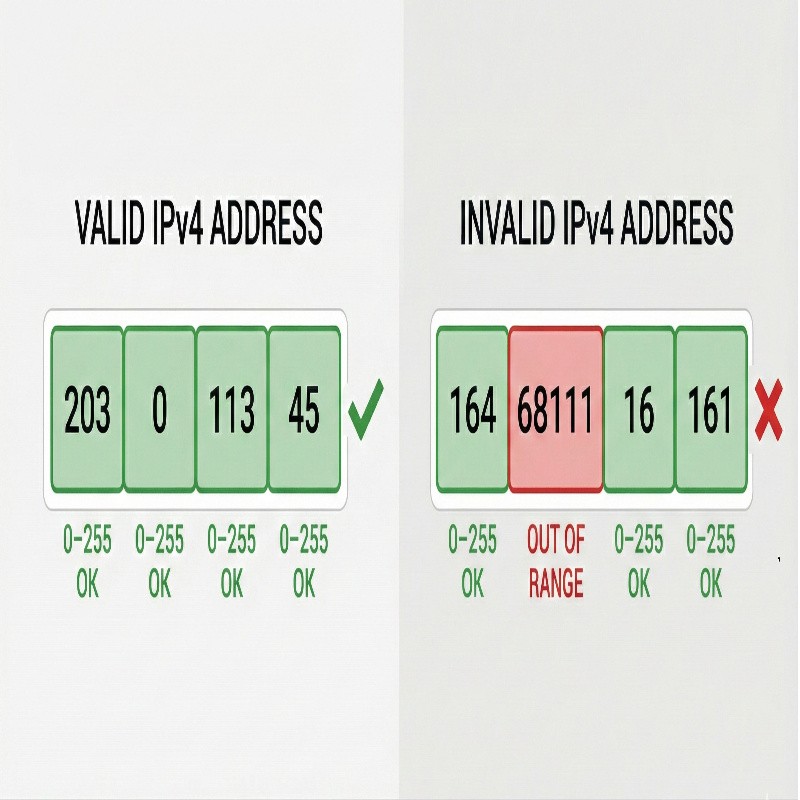

IPv4 addresses follow a very specific structure: four numbers separated by periods. Each of those numbers is called an octet. Behind the scenes, each octet represents 8 bits, and together the four octets form a 32-bit address. But you don’t need to think in binary all day to work with them—you just need to understand how the ranges work.

The allowed range for each octet is from 0 to 255. That’s it. If any part of the address goes below 0 or above 255, the address is invalid. So when you see a sequence where one “octet” is something like 68111, you can be sure it’s breaking the core rule. In a case like 164.68111.161, the second “octet” is simply too large to be part of a valid IPv4 address.

Why 0–255 Matters So Much

The 0–255 range isn’t arbitrary. It comes straight from how computers store data in binary. Eight bits can represent 256 different values, from 0 to 255. Each octet in an IPv4 address is exactly eight bits long, which is why you see that same range repeat four times.

Because this rule is baked into the foundation of IPv4, any system that validates addresses will reject values outside that range. When the earlier pillar piece talks about 164.68111.161 failing the test, this is exactly what’s going on: one of the octets spills over the allowed limit, so the whole sequence collapses as a valid address.

Dot-Decimal Notation: How IPv4 Is Written

The most common way to write IPv4 addresses is called dot-decimal notation. That just means each octet is shown as a decimal number, with dots in between. For example:

10.0.0.1172.16.5.20203.0.113.45

This format is meant to be readable by humans while still mapping neatly to binary under the hood. The structure is strict enough that most people can glance at it and feel whether something is off. When you compare a normal-looking address with something like 164.68111.161, that extra-long octet stands out, even if you don’t immediately remember the exact rule.

Classes, CIDR, and Address Ranges

Historically, IPv4 addresses were divided into classes (Class A, B, C, and so on). These classes controlled how many bits were used for the network portion versus the host portion. While this old “classful” system is less important today, it still shows up in older documentation and training materials.

Modern networks use something called CIDR (Classless Inter-Domain Routing) instead. A CIDR notation looks like 192.168.1.0/24, where /24 tells you how many bits are used for the network part. Even in these more flexible schemes, though, the basic rule about 0–255 per octet doesn’t change. That’s why a malformed sequence such as 164.68111.161 fails regardless of how you try to slice it.

Private vs Public IPv4 Addresses

Not every IPv4 address is meant to be visible on the open internet. Some ranges are reserved as private addresses, meant to be used only inside local networks. You’ll often see these ranges in home routers and corporate LANs:

10.0.0.0 – 10.255.255.255172.16.0.0 – 172.31.255.255192.168.0.0 – 192.168.255.255

Everything outside these ranges is potentially routable on the public internet (subject to allocation and routing policies). But again, whether an address is private or public, it still has to stick to the same structural rules. A “private” address like 10.300.1.5 is just as invalid as 164.68111.161 because the 300 is out of bounds.

How Systems Validate IPv4 Addresses

When applications, firewalls, or APIs accept an IP address as input, they usually perform some form of validation. This might be as simple as checking that there are four numeric chunks separated by dots and that each chunk falls within 0–255. In more careful implementations, there may be extra checks for reserved or special-use ranges.

In code, this validation often depends on regular expressions, parsing libraries, or built-in networking utilities. If any part of the address fails these checks—wrong number of octets, characters that aren’t digits, or values like 68111 that break the allowed range—the input is rejected or flagged. When the pillar article talks about malformed entries turning up in logs, this is usually the stage where they’re caught.

Why Invalid Addresses Still Show Up

Given all these strict rules, it might seem like invalid addresses shouldn’t appear at all. But in practice, they do—often. Sometimes it’s just a typo when someone copies an address into a configuration file. Other times, a script concatenates or parses data incorrectly, and a number that was never meant to be an octet ends up in the wrong place.

There’s also a more intentional side to this. As discussed in the main piece on 164.68111.161, invalid or fake IP addresses can be used as placeholders in testing environments. Developers use them to simulate traffic without accidentally targeting a real system. In security contexts, they can serve as part of honeypots or decoy setups, which ties neatly into content about honeypot decoy IPs and deception tactics.

How IPv4 Structure Connects to Cybersecurity

Understanding the IPv4 address structure isn’t just a theoretical exercise. Security tools rely on it heavily. Intrusion detection systems, firewalls, and SIEM platforms all parse IP addresses constantly, deciding which traffic is normal and which looks suspicious.

When something doesn’t look right—say, a repeated attempt to use malformed addresses, or strange patterns involving sequences like 164.68111.161—it might indicate a misconfiguration or even an attacker probing for weaknesses. Knowing how addresses are supposed to look makes it easier to spot what doesn’t belong, especially when combined with the ideas in a deeper cybersecurity-focused article.

Common Mistakes with IPv4 Addresses

Even experienced teams occasionally slip up with IP addresses. Some of the most common mistakes include:

- Using values over 255 in one or more octets.

- Typing three or five octets instead of four.

- Mixing up IPv4 and IPv6 formats.

- Misreading or miscopying addresses from documentation or logs.

These mistakes can lead to confusing error messages, unreachable services, or odd entries in monitoring tools. When developers then go back through logs and stumble on an address like 164.68111.161, they may start to wonder whether it’s just a typo or something more meaningful—exactly the kind of question explored in the pillar article.

Why Addresses Like 164.68111.161 Raise Questions

There’s a reason that particular sequence has sparked so much discussion. It looks close enough to a real IP address to feel familiar, but it fails just obviously enough to seem intentional. That middle “octet” is so far above 255 that it almost looks like a code, an ID, or a version string that just happens to be in a dotted format.

This is where the line blurs between IP addresses and other dot-separated structures, like software version numbers or internal identifiers. In some environments, people re-use the dot pattern for things that aren’t IPs at all, which is why it’s easy to confuse them at a glance. A separate deep dive into software versioning systems helps unpack how those patterns evolve and why they can be mistaken for network addresses.

IPv4 vs IPv6: A Quick Contrast

Another reason confusion happens is that IPv6 exists alongside IPv4 and uses a very different notation. Instead of four decimal octets, IPv6 uses groups of hexadecimal numbers separated by colons. An IPv6 address might look something like 2001:0db8:85a3::8a2e:0370:7334, which is clearly a different structure.

A sequence like 164.68111.161 doesn’t fit IPv4, and it doesn’t fit IPv6 either. That puts it in a kind of gray area—familiar, but structurally homeless. Understanding both address families makes it easier to spot when something truly doesn’t belong to either world.

How Developers Can Handle IPv4 Safely

For developers, getting IPv4 handling right comes down to a few habits:

- Always validate user input that claims to be an IP address.

- Rely on battle-tested libraries rather than writing custom parsers from scratch.

- Log validation failures clearly so malformed values can be investigated later.

- Avoid using “almost valid” IP-like strings as identifiers unless clearly documented.

These practices reduce the chances of strange values creeping into production systems. They also make it easier to debug issues when they do appear—especially if the logs clearly show whether something like 164.68111.161 was rejected as invalid or processed in some other way.

IPv4 Structure in Monitoring and Logs

Monitoring tools that collect large volumes of network data depend heavily on accurate IP parsing. Dashboards, alerts, and reports often group traffic by address, subnet, or range. If malformed addresses keep appearing, they can skew metrics, confuse dashboards, or hide real problems.

That’s why operations teams typically implement filters or rules to clean up obvious anomalies. Knowing the IPv4 structure lets them quickly mark certain patterns as noise, while still paying attention to recurring oddities that might hint at misconfigurations or probing activity.

Putting It All Together

Once the structure of IPv4 is clear—four octets, each from 0 to 255—it becomes much easier to interpret what you’re seeing in code, logs, and configuration files. Valid addresses stand out as clean, predictable, and usable. Invalid ones, like 164.68111.161, become red flags that prompt questions: Is this a typo, a test value, a security decoy, or something else entirely?